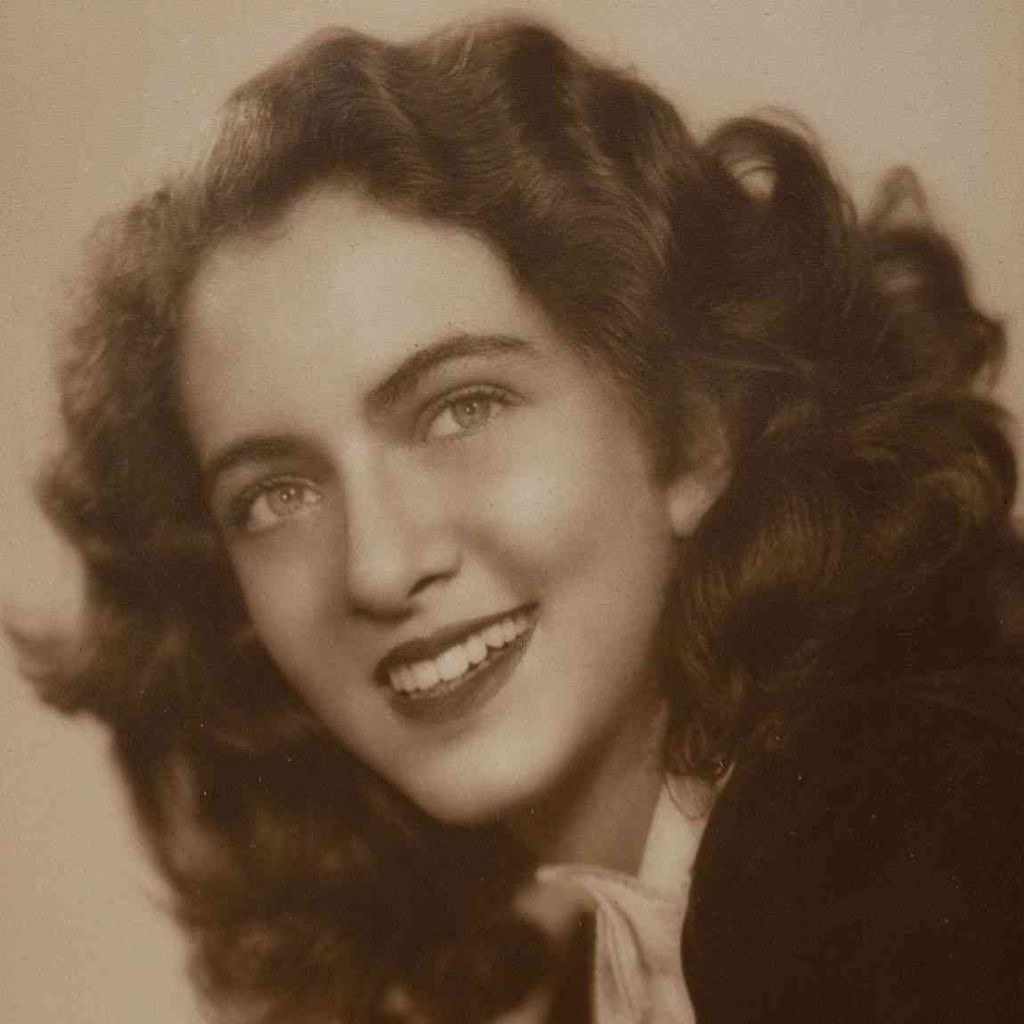

Alvia Grace Golden

1930 - 2025

Share Alvia Grace Golden's obituary with others.

Invite friends and family to read the obituary and add memories.

Stay updated

We'll notify you when service details or new memories are added.

You're now following this obituary

We'll email you when there are updates.

Please select what you would like included for printing:

Share Alvia Grace Golden's obituary with others.

Invite friends and family to read the obituary and add memories.

Stay updated

We'll notify you when service details or new memories are added.

You're now following this obituary

We'll email you when there are updates.

Please select what you would like included for printing:

Alvia Grace Weinberger Golden, consummate raconteur and wordsmith, poet, businesswoman, marketing executive, rabblerouser, and beloved partner, mother, grandmother, aunt and friend, died in her home-of-the-heart, New York City, on November 23. She was just over two weeks shy of her 95th birthday.

Alvia’s list of achievements is remarkable, particularly for a woman of her generation. In the 1950s, divorced and needing to support her three small children, she worked first as off- and then on-air talent for a small regional radio station, then was hired as a copy writer in a Philadelphia ad agency. In 1963 she and two partners set up their own agency, developing Lane Golden Phillips into a multi-million dollar business. As creative director, Alvia launched what arguably may be the first marketing use of the phrase “Women Mean Business” in a hugely successful ad campaign for a regional bank.

When the partners sold the agency in 1982, Alvia took a position with the marketing division at Philadelphia-based pharmaceutical company Smith Kline & French (now GlaxoSmithKline), developers of Thorazine and the ulcer pill Tagamet, among others. In an overwhelmingly male-dominated field, she moved quickly through the ranks even as the economic shakeups of the late 1980s led to massive layoffs. She served for a time as Executive Speech Writer for the company’s top leadership, then was named Marketing Director for the first managed healthcare department in any American pharmaceutical company.

Alvia enjoyed the challenges of advertising, “pitching” ideas as well as creating campaigns, but she had no illusions about her work. She once wrote a friend to say she’d just finished her first reading assignment for a class she was auditing, called Propaganda and the Mass Media. “Bottom line,” she said, “I spent my entire career writing, promoting and profiting from (drum roll) Propaganda.”

What mattered to her was a creative life, a life of the mind. Growing up, she’d gone — first with her mother, then on her own — to innumerable Broadway plays, sitting in the cheap seats to see the likes of Ethel Merman, Laurette Taylor and Helen Hayes. (In her 80s, she wore a t-shirt that said, “I speak fluent show tunes.”) She’d gone to college, at age 17, at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon), with aspirations to “tread the boards.” In the Institute’s small, intimate Fine Arts program, she came to know actors and artists, forming lifelong friendships with many of them. From her earliest working days, she spent her discretionary income on art — affordable pieces, drawings rather than paintings, surrounding herself with small gems by Calder, Isabel Bishop, Nevelson and others. She was a ravenous reader throughout her life. In her late 80s and 90s, when health and mobility issues slowed her down, she pestered friends incessantly for book recommendations, sometimes reading a book a day — usually on her iPhone.

Two things happened during Alvia’s late forties that blasted open the doors to that longed-for life of the mind: First, she met Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, who became the love of her life and her partner of 45 years. The bond between Alvia and Carroll was extraordinary to witness, rare and potent as the aurora borealis or a double rainbow. Alvia once wrote, “I realize it’s fashionable to call this bond that doesn’t want to stretch all that far, ‘co-dependency,’ or some other disease state, and maybe after all it is a sickness, since when we can’t be in contact even for as much as a whole day, we both suffer, but I am old enough to know that some day whether we want it to be or not it will be ‘cured,’ and that being the case, I’ll take the disease.”

In Carroll, a professor of history whose groundbreaking work helped change the very nature of historical research and open the field of feminist scholarship, Alvia found an intellectual partner who also matched (and sometimes outmatched) her in stubbornness, physical energy, cooking skill and political belief. Carroll introduced her to an academic milieu with a strong political bent. Alvia often felt intimidated, and sometimes frustrated, in such company — she once wrote about a couple Carroll had invited for dinner, who “will appear here, dressed in silk and wearing jewelry and being intelligent and well-spoken, and leave me feeling bored and angry and wanting to say dirty words because we’ll be talking about politics and I want to talk about nonsense, like does anybody have any idea of what the hell we’re all doing here.” But despite herself she thrived in that milieu, challenging herself to extend her own learning, and charming one and all with her wit and down-to-earth insights.

The other life-altering event: She enrolled in poetry writing classes at New York’s 92nd Street Y, driving up from Philadelphia once a week to study with Audre Lorde and Jean Valentine. Valentine, who also taught in the writing program at Sarah Lawrence College, encouraged Alvia to apply to the college’s graduate poetry-writing program, even though it took on only a handful of students each year. Alvia did, and was accepted in 1977, studying with Valentine, poets Jane Cooper and Thomas Lux, and the force of nature that was writer/poet/activist Grace Paley. Alvia went on to publish poems and stories, but having space and support for writing and sharing her work mattered even more. “The poetry makes my life make sense to me,” she said.

Alvia was always driven to make a difference. She was a longtime supporter of the ACLU and other progressive groups. She mentored and supported her female employees. And she volunteered with civic and community organizations in both Philadelphia and New York, including the Juilliard School’s Drama Council. When Carroll accepted a professorship at the University of Michigan, the couple moved from Philadelphia to Ann Arbor. There, Alvia volunteered with a local law office whose work focused on abuses in Michigan’s criminal justice system. She conducted research for a class-action suit on behalf of women prisoners who’d been systematically abused by their guards, researching transcripts to discover legal errors in prison officials’ testimony, interviewing clients in prison to gather facts, and summarizing and editing testimony for court appearances, including a presentation by the firm’s lead attorney before the U.S. Supreme Court. Alvia’s work contributed to the suit’s success, which resulted in a $100 million settlement from the Michigan Department of Justice and the Michigan Corrections Organization. In 2006, after Alvia and Carroll moved back east to New York, Alvia trained with the state’s Long Term Care Ombudsman Program, which is dedicated to protecting people living in long-term care facilities. Assigned to a facility on Manhattan’s upper East side, for more than 15 years she acted, in her words, as “a firm but tactful liaison” on behalf of residents — not a few of whom were younger than she — and their families to resolve concerns and conflicts with the facility’s management.

Though she was born in the Bronx and grew up in the neighboring suburb of Mount Vernon (where she went to school with Dick Clark and “Marty” Duberman), Manhattan was Alvia’s natural habitat. She loved the friends she and Carroll made in Ann Arbor but chafed at what seemed to her its small town atmosphere. Accustomed to driving like a New York cabbie, in Ann Arbor she accumulated an alarming number of traffic citations. Finally able to settle in Manhattan, she took full advantage, from daily shopping with the neighborhood fishmonger, cheese shop and on-the-street fruit vendors to frequenting off-Broadway theater, museums and readings. When she was no longer able to walk any distance or negotiate subway stairs, she used her motorized scooter (which she dubbed Rocie, short for Rocinante), often terrorizing pedestrians when she used the sidewalks or doing battle with bike messengers in the bicycle lanes. She came to love the city bus and the views it offered of the city and its inhabitants; she was especially delighted on the rare occasions when she was able to surrender her seat to someone older than she.

One of the strongest threads in Alvia’s life was her value of, and dedication to, family and friends. She held on to loved ones as greedily as some people cling to money and power. Family included Carroll, her partner of 45 years; her father Emanuel and beloved (and much dreamed-about) mother Sophie Weinberger; her brother Roy and wife Dorothy; her adored children, Gregg, Margaret and Richard (Rod) Golden and Leah Rosenberg, and their spouses and partner; her granddaughter, Ava, with whom she maintained weekly Zoom sessions to read books and talk about Ava’s life; and her brother’s children, Beatrice and Gary, and their spouses and offspring. The litany of friends, living and dead, notably includes a circle of near-lifelong friends from her college days, all of whom Alvia outlived and mourned; Betty Zeidman, a friend-of-the heart from Alvia’s earlier Philadelphia days; a group dubbing themselves the Warthogs (likely Alvia’s coinage), who worked together in Philadelphia and who continued their marathon get-togethers via Zoom when they began to disperse across the country; the Dianas (another Alvia label), who audited classes together at Hunter College and the Alliance Francaise, met for lunch after class, and went together to the opera and theater; and Texas friends Martha and Cathy, close companions ever since Alvia and Martha’s time together at Sarah Lawrence. There are many, many more friends, equally dear but too numerous to list.

To say that Alvia lived life to the fullest is an understatement. The tagline with which she closed all her emails (a quote from an old favorite, Archie and Mehitabel), fit perfectly: “wotthehell, wotthehell / there’s a dance in the old girl yet / toujours gai toujours gai.” Though she worried often about death and dying, especially as she entered what she called the “cohort of loss” — that age in which long-time loved ones decline and fall at an ever-rapid pace — she finally made peace with the inevitable, telling loved ones she no longer feared death and, in the end, slipping quietly away.

If she were writing her closing lines, Alvia likely would say something piercingly profound. And/or, equally likely, she might repeat this line from the closing of one of her many, many letters to loved ones: “As they say in the Oulde Cuntrie… May the road rise up and miss ye! Happy Day to yez! Peace & much much cabbage, Alvia."

Alvia Grace Golden's Guestbook

Visits: 2

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the

Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Service map data © OpenStreetMap contributors