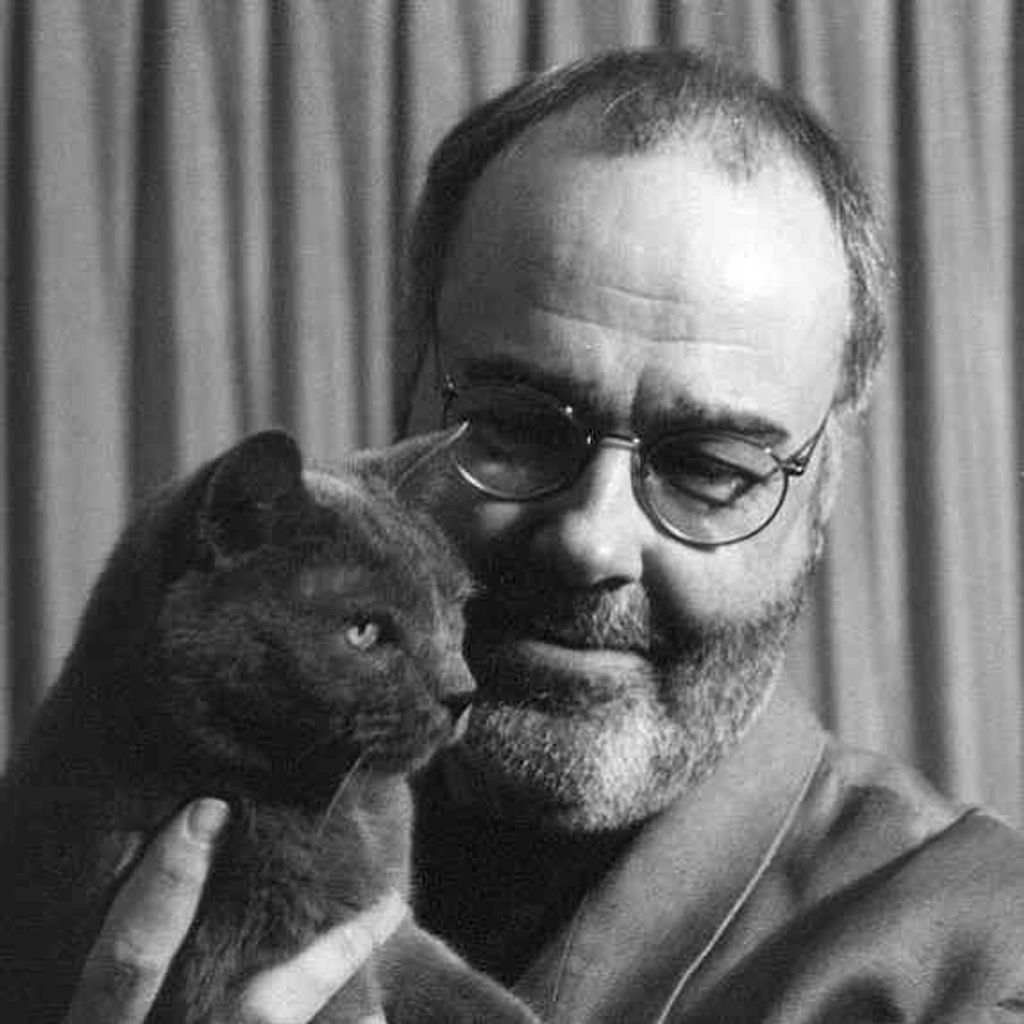

James Sallis

1944 - 2026

Share James Sallis's obituary with others.

Invite friends and family to read the obituary and add memories.

Stay updated

We'll notify you when service details or new memories are added.

You're now following this obituary

We'll email you when there are updates.

Please select what you would like included for printing:

Share James Sallis's obituary with others.

Invite friends and family to read the obituary and add memories.

Stay updated

We'll notify you when service details or new memories are added.

You're now following this obituary

We'll email you when there are updates.

Please select what you would like included for printing:

James Sallis, renowned writer, teacher and musician, died January 27, 2026 at the age of 81 in Phoenix, Arizona after a long illness.

Best known for his Lew Griffin detective novels and the 2005 novella Drive (the basis for the 2011 Nicholas Winding Refn film starring Ryan Gosling), Sallis leaves behind a broad body of work that includes eighteen novels, numerous short story and poetry collections, a biography and translations. He was a true man of letters in the old-fashioned sense, a polymath who devoted his life to the printed word.

Sallis’s characters were often survivors who somehow managed to go on, despite heavy odds. He was cosmopolitan and sophisticated, yet remained in many ways a Southern gentleman, with impeccable manners and an easygoing warmth. Sallis had an unwavering curiosity about people, and often carried a small notepad to capture little details — images and snippets of conversations — that interested him.

Born December 21, 1944 in Helena, Arkansas, James Chappelle Sallis, known to his friends as Jim, was preceded in death by his parents, Horace C. Sallis and Mildred Liming Sallis, his brother John Sallis (the noted philosopher), and son Dylan. He is survived by his loving wife of 35 years, Karyn Sallis.

The music of the South, the Delta blues he heard on Helena’s seminal King Biscuit Time radio broadcast (which featured artists such as Sonny Boy Williamson II and Robert Jr. Lockwood), remained deeply imbedded in his DNA. He would go on to publish several books of musicology, The Guitar Players (1982), Jazz Guitars (1984) and The Guitar in Jazz (1996). Sallis himself was a talented musician and played a variety of stringed instruments, including guitar, dobro, mandolin, fiddle and banjo. Jim was at his best as a performer when he played backup for bands and soloists around the valley, appearing on the albums of several respected Arizona musicians. His trio, Three-Legged Dog, performed at coffee shops and folk festivals around Arizona.

Both Sallis and his brother John, bookish outsiders in parochial 1950s Helena, were destined to leave their hometown behind. For Jim, the ticket out came in the form of a scholarship to Tulane University. Sallis fell in love with New Orleans, a city that he would return to again and again. He met first wife Jane while at Tulane. Sallis would ultimately leave without a degree, briefly attending the University of Iowa before deciding to focus full-time on his writing.

In the mid-1960s, writer Michael Moorcock invited Sallis, only twenty-one at the time, to London to become the fiction editor at New Worlds, the influential “New Wave” science fiction magazine. It was an exciting time for Sallis, who was already developing a name for himself as a short story writer.

1970 saw the publication of Sallis’s first collection of stories and poems, A Few Last Words. The next few years would be extremely productive ones. Now back in the States, Sallis published a steady stream of reviews, essays, and short stories and edited several story anthologies. Harlan Ellison became an early supporter of Sallis’s work, and remained a committed friend for the rest of his life. Damon Knight and Kate Wilhelm, who ran the Clarion Writers Workshop, also championed and briefly housed the young writer.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Sallis moved around quite a bit, ultimately settling in Texas. To supplement his writing, he worked as a respiratory therapist, in adult units and in neonatal care. He would draw upon this experience in his novels and also in his essay collection, Gently Into The Land of the Meateaters. Sallis continued to work off and on as a respiratory therapist for many years.

It was while living in Fort Worth that he met and was charmed by Karyn Smith, who worked at a local print shop. They quickly became inseparable. Married in 1991, the couple moved to New Orleans; the following year, The Long-Legged Fly was published. Attracting attention from major reviewers and kicking off his acclaimed Lew Griffin series, Fly would be a turning point in Sallis’s writing career. His first full-length crime novel, it was unlike anything that had been published before.

A respected critic, Sallis penned book reviews for The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, Fantasy & Science Fiction, and other periodicals and served as a judge for the Philip K. Dick Award in 2019.

As a writer, Sallis drew on influences from everywhere and disliked labels. He sometimes described art and literature as a grand buffet, with high and low art occupying equal space at the table. While he cited novels such as James Joyce’s Ulysses and William Gaddis’s The Recognitions as favorites, and was naturally drawn to surrealist fiction and poetry, he also loved and embraced genre fiction of all kinds: noir, science fiction, westerns. He felt a real kinship with writers such as Jim Thompson, David Goodis and Theodore Sturgeon, and wrote about them extensively in his critical work. His 2001 biography, Chester Himes: A Life (a New York Times Notable Book of the Year) brought renewed interest to the neglected master’s work.

His 2005 novella Drive, originally rejected by his publisher, ultimately found a home at The Poisoned Pen Press. It would go on to become his best-known work (The New York Times called it “a perfect noir novel”). Sallis’s work earned him a fiercely devoted readership around the world. In 2007 he received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the annual Bouchercon Awards. The Killer is Dying (2011) won France’s Grand Prix de la Litterature Policiere as well as the UK’s Hammett Award. While he loved the film version of Drive and enjoyed the exposure it brought to his work, Sallis wasn’t particularly interested in self-promotion or in writing for a commercial audience. He disliked having author blurbs on his books (although his publisher managed to override this occasionally).

*A brilliant and intuitive instructor, beloved by his students, Sallis taught creative writing at Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles, at Phoenix College for fourteen years, and in workshops for the Piper Center for Creative Writing at Arizona State University. He encouraged his students to dig deep within themselves for material. “Write about what scares you,” he admonished. “Write about what you don’t understand.” Sallis wrote constantly, and he encouraged his students to do the same. In 2015, he left Phoenix College when he refused on principle to sign a state loyalty oath.

As serious as he was about his work, Sallis had a great sense of humor and an infectious laugh. He had an appreciation for the absurd, loved puns, and was an aficionado of bad action films ("Roadhouse" being a particular favorite) and cheap poorly-dubbed martial arts movies.

Fond of animals, Sallis and his wife Karyn kept many cats as pets, and provided committed care to a community of ferals in his Phoenix neighborhood. Several of the felines, initially leery of humans, yielded under Sallis’s gentleness and sought him out for attention. He had infinite patience with cats, and dedicated his 2016 novel Willnot to them.

James Sallis was dedicated to his art and he led by example. As Paul Oliver of Soho Press expressed it, Sallis was “the platonic ideal of what a writer can be.”

On his desk was a scrap of paper where Jim had jotted a note to himself of a phrase to be used in the latest manuscript: “I spent the morning taking myself too seriously, which left the question how the afternoon and evening might be occupied.”

The world is diminished by his passing.

---

If you wish to donate in his memory, the family suggests the ACLU and the Humane Society as worthy charities that Jim valued.

James Sallis's Guestbook

Visits: 38

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the

Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Service map data © OpenStreetMap contributors