Marty Zatz was a scientist, an immigrant, and a Jew. He loved language, his family, and other people's stories. His began among the embers of World War II and the Holocaust. His parents, Ruchel and Reuven Zatz, had survived years in Nazi camps and those of their local proxies, and then returned to their home Bessarabia region at the intersection of modern-day Moldova, Ukraine, and Romania. Aiding their survival were Reuven’s skills as a farmer, which facilitated foraging for potatoes, and Ruchel’s ability as a polyglot to understand more than their guards realized, including through knowledge of German she picked up both from Yiddish and early training to be a pharmacist.

Ruchel and Reuven had lost their first child, and each lost a brother, to the camps and the war. A twin sister was then born alongside Marty, but she did not survive the extreme hardship of their first months. Due to the disruptions of war, the earliest family or official documents begin only later, but January 10, 1944, is Marty’s consistent birth date, while birth locations named include Chernowitz, Bershad, and Secureni. As an adult, Marty’s own records were meticulous and organized. The decisive proof of the dementia that defined his last years lay in the disarray of his tax documents and piles of unsorted mail that his family encountered upon the first in-person visit in 2021 after COVID shutdowns.

As the Iron Curtain came down around 1946, Reuven insisted that the family flee West. They made their way eventually to a displaced persons camp in Italy, where Marty spent a couple of childhood years alongside his parents, maternal grandmother Scheindel, and Fanya, the widow of Ruth’s murdered brother, Moishe. There, too, was Fanya’s daughter Ada, who had survived the war in an orphanage in Bucharest and was miraculously reunited with her mother; Marty and Ada were as close as siblings. The family took advantage of whatever opportunities they could find in the camps, including a trip to ancient ruins that Marty pronounced boring as just “stones and bones,” which also rhymes in Yiddish.

Marty’s first language was Yiddish, with exposure to Russian and Italian, before learning English. He was known initially as Moishe or Musia, becoming Marty as an “American” name when he arrived in the United States, where his parents became Ruth and Reuben.

The family was able to come to the United States in Fall 1949 as refugees with a family sponsor, Ruth’s sister, Pola Greenstein (née Fish), who had been sent to the U.S. alone as a teenager just before the War. Fanya and Ada left for Israel. While most refugees traveled by ship, Ruth’s health was precarious. She still suffered from a back that had been broken by a German soldier’s rifle butt, and she was late in pregnancy. As a result, and with the assistance of HIAS (the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society), the family was able to cross the Atlantic by military cargo plane, with Marty’s first North American memory being the blast of cold air through an open cargo door as they stopped for fuel in Newfoundland.

Now enlarged by the birth of Marty’s brother Carl in November 1949, the family stayed a few years with Pola’s family in Providence, Rhode Island, while Reuben worked in a local store and then tried to establish himself in New York City. Marty’s memories from this time were largely of hardship, xenophobia, and catching sight of his father only in the middle of the night; he harbored a lifelong antipathy for Providence.

When Marty was in 5th grade, the family moved to the Bronx, where Reuben worked as a peddler/salesman, selling furniture in Spanish Harlem on commission/layaway, as he did for the remainder of his working life. Reuben learned to speak Spanish with a Yiddish accent, and his English lagged behind his Spanish. Ruth mostly cared for the family and home, but she was proud of her unusual educational achievements for her time, as an Old-World Jewish girl who went beyond high school to train as a pharmacist. Later, she would become an active and proud volunteer in many community settings.

As a Jewish, immigrant, non-native English speaker, and newcomer, Marty remembered being bullied by local kids in his Bronx neighborhood. He worked hard to learn unaccented English and excel in school. He attended Yeshiva (Jewish religious school) through 8th grade, where he graduated as valedictorian, made lifelong friends, and acquired a taste for argumentative contention and precision . He switched over to public school with his admission to the Bronx High School of Science. His parents drove Marty hard in school—he recalled reporting that he had scored a 98 on a test and receiving in reply, “what happened to the other 2 points?”—and were proud of his achievements; Ruth kept his report cards with her for decades. Marty was on his way to a scientific career, yet when he reminisced about his early education, it was his high school training in journalistic writing and his college coursework in the social sciences that he reminisced about most fondly.

The family struggled economically. Marty recounted not eating in a restaurant or taking a vacation until he was an adult. Although he was driven and excelled, Marty also experienced little control or say in his early life. After a teenage summer working in a US Post Office, he committed to avoiding any job where he had to ask permission to use the bathroom. Reflecting on his alienation when visiting Princeton while exploring college possibilities, Marty said that as a Jewish immigrant, he kept looking for the service entrance. He enrolled at Columbia, with the support of scholarships and the ability to live at home.

Marty met Marion Mund at Bronx Science, and they began dating at the end of high school. Shortly after he graduated from Columbia and she from Barnard, they married in 1965 at ages 21 and 20. Marty went on to Albert Einstein College of Medicine, on full scholarship in a new program allowing students to simultaneously earn an MD and PhD, in medicine and pharmacology, and gain a strong identity as a “Mud Phud.” At the same time, Marion earned her PhD in immunology at Cornell University’s New York medical campus. The couple moved on to Yale University, where Marty did a medical residency in psychiatry and Marion continued her research. Their first child, Noah, was born in New Haven in 1972.

Marty decided to pursue scientific research rather than medical practice. In 1974, he moved to the National Institute of Mental Health via a position in the federal Public Health Service. Thanks, in part, to that service and his parental status, Marty sidestepped direct Vietnam-era military service. At the NIH, Marty entered the field of research on circadian rhythms (the body’s daily cycle) under the mentorship of Nobel Prize winner Julius Axelrod, transitioning to a permanent civilian position and spending the rest of his career there. Much of his research focused on the regulation of melatonin production in the pineal gland, using cells extracted from chickens as a model organism. Devilish and averse to putting on airs, when asked by a stranger what he did for a living, Marty typically said, “I kill baby chickens.”

The family settled in Bethesda, Maryland, in a suburban neighborhood across the street from the NIH. Daughter Sara was born in 1976. While committed to providing his children an upbringing with more freedom and less hardship than his own, Marty also insisted that they not take it for granted, occasionally making a point of rejecting a creature comfort that, while attainable and conventional, seemed to him an indulgence.

Reuben died in 1978, and Ruth, who still suffered from chronic health problems, moved to an apartment in Rockville in the early 1980s to be closer to Marty and her grandchildren. When Noah and Sara were younger, she came over regularly to care for them, make dinner, and light Shabbat candles on Fridays. Marty and his mother had a devoted but difficult relationship, with Marty ensuring her care as her health declined and until her death in 2005. Ordinarily, they spoke English in front of others, but Yiddish was the language they reverted to for arguments.

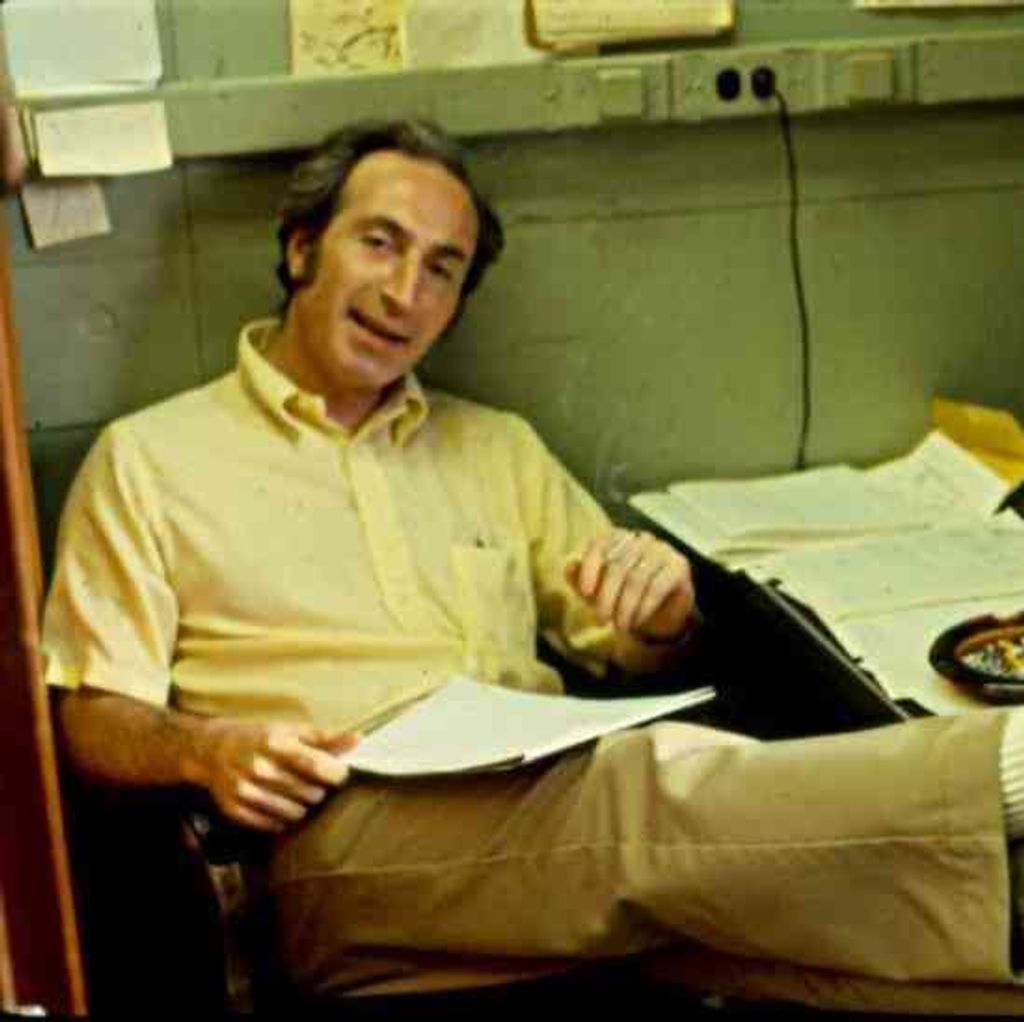

Marty’s career was long and steady. He was known for being an excellent mentor to younger scientists and a valued interlocutor, though also quite intimidating intellectually. Colleagues consistently recall the sharpness of both his analysis and his humor, including a penchant for lobbing insightful but sometimes devastating questions from the back of lecture rooms at scientific meetings.

Marty was devoted to his science but eventually felt he was not flourishing at the NIH, leading him in 2004 to retire early from the lab. He continued joyfully for another decade as a celebrated editor of the Journal of Biological Rhythms (JBR), the main academic publication in his field. He threw himself into editorial work and continued participating in scientific meetings, especially those sponsored by the Society for Research on Biological Rhythms. A meticulous and demanding editor of research articles, Marty also explored his broader interests in the philosophical and institutional aspects of science by penning a series of probing and reflective editorials (preserved at srbr.org/publications/jbrish). Marty refused to take anybody, including himself, too seriously, and his mischievous and irreverent wit was reflected in his invention and publication of fictional letters to the JBR editor from meaningfully made-up writers, often chiming in to criticize one of Marty’s own recent editorials.

Noah and Sara both attended local public schools in Bethesda (Wyngate, Tilden, and Walter Johnson). The family had two cats in whom Marty had little interest, and later a beagle named Jessie whom Marty adored. The family regularly took trips into Washington DC for museums and cultural events, especially when hosting visitors. Marty often insisted on driving downtown rather than taking the nearby Metro in some kind of ritual and stubborn pride in being a New York driver who rejected his earlier reliance on the New York City subway. The family was distinctly neither athletic nor outdoorsy, though Marty tried gamely but not very successfully to do appropriately American things like go fishing with his son, often resulting in humorous and only mildly dangerous failures.

The family did not watch much TV or regularly listen to music. The radio was set to news, and there was no TV in the living room. Marty did not follow sports, but the family watched the Super Bowl every year because that was what you were supposed to do, though Marty was clearly more interested in Cosmos and National Geographic. The family was able to take a couple of big international trips, and a few more to marquee U.S. National Parks. Marty enjoyed travel and was an avid photographer, readily getting distracted or delayed, and enjoyed editing and curating slides for post-vacation slide shows.

With the crucial exception of air conditioning, Marty hated many “modern conveniences” that he deemed intrusive or unnecessary, and therefore the family was late to having an answering machine, VHS player, call waiting, CD player, etc. He didn’t see why he needed to answer the phone just because it was ringing, and Marty basically never used a cell phone even when everyone else really wished he would. He stubbornly resisted email for a while but eventually was worn down by his children when they left home; he later became a prolific correspondent and excessive forwarder of jokes.

Noah left home to attend Cornell for college, and then Sara went to Bryn Mawr. Marty was consistently proud of their academic and professional achievements while making clear that these were not what ultimately mattered most to him. He encouraged pursuit of passion over cautious instrumentalism. A few years after both children had left for college, Marty and Marion divorced.

Noah married Jessica Cattelino in 1995. Sara married Adam Nadel in 2009. Noah and Jessica are parents to Mica (16) and Rosie (14). They live in Culver City, California, where Noah and Jessica are both UCLA faculty, he in law, she in in anthropology. Sara and Adam are parents to Raya (13). They live in Jackson Heights, Queens, NYC. Sara works as the Artistic Director, Engagement for the non-profit theater company Pink Fang (formerly Ping Chong and Company), and Adam is a photographer and teaches history of photography at Queens College and other institutions. Marty loved his grandchildren dearly, delighted in teaming up with them against their parents, and endeavored to impart his love of Yiddish, wordplay, curiosity, and careful observation.

Around 2000, Marty met Marcia Bordman via a classified ad in the Washington Post, and they became devoted partners. In their early years, they enjoyed traveling widely together, including many destinations of their choosing across the U.S. and the world. Marcia would also accompany Marty to scientific conferences and enjoyed times with his friends and colleagues. Marty likewise became integrated into Marcia’s wide circle of friends in a dizzying array of reading, poetry, and study groups.

Marcia was an English professor at Gallaudet University, and they were a hilarious couple, their literature vs. science shticks coexisting with a shared foundation of intellectual curiosity, deep cultural pursuits, Jewish identity, humor, and love of language. More than anything else, they simply enjoyed one another’s company and could tell each other stories and analyze text together for hours, often to the detriment of whatever schedule they and others might have been on. As Marty suffered from dementia and Marcia from kidney disease, they were devoted to each other’s care as long as, and even beyond, when they were able. Even as Marty lost his way with simpler tasks, he somehow summoned the capacity to perform daily maintenance on Marcia’s complex home dialysis equipment. Marcia passed away in 2023, months after Marty entered a memory care community nearby.

Throughout his life, Marty retained a passion for intellectual pursuits, a sense of curiosity, a strong sense of ethics and Jewish culture and social justice values (without maintaining regular religious observance), a love for wordplay and Yiddish language and humor, and a disdain for physical exercise, green vegetables, and other forms of conventional rule-following.

He remained devoted to his family, and to the idea of the possibility of the “American Dream.” He always rooted for the underdog and loved a “David and Goliath” story. He was a bit of a contrarian, with facial expressions and tone that could seem dismissive or scary when he was just curious and furrowing his brows. He also could have a temper in the face of perceived foolishness, disrespect, or incompetence. He appreciated people who could go “toe to toe” with him with intellectual debate and/or wisecracks. Were he reading this, he would have a lot of editorial suggestions and criticisms, and would not be afraid to share them.

When people asked his hobbies, his family would say “his hobby was being smart,” which made the cognitive loss from dementia especially devastating. Nonetheless, he somehow maintained his essential qualities even as dementia robbed him of his memory of even his most basic biographical facts. While living in memory care communities, he observed, marveled at, and formulated curious questions about the world around him, especially the clouds and the trees. He urged his grandchildren to “pay attention” and “ask questions,” and he delivered endlessly earnest lectures about Yiddish usage, especially the word “takeh,” which means “really” but can have a million variations in meaning depending on intonations. He got and appreciated jokes, and demanded that questions be well specified. Inevitably, if a loved one or a medical professional asked how he was feeling, he would respond, “compared to what?”

Perhaps most movingly, even as the disease robbed him of precious time, there flowered in Marty a resolute kindness and gratitude for what remained. Even as he was poked, prodded, and assessed for reasons he did not understand, he consistently made a point of saying “thank you” and praising a job well done. When his grandchildren had to remind him not only of their names but their existence, he smiled warmly and said not only that he was delighted (if also surprised) to be a zeyde but that he was happy to be their Zeyde.

After a steep decline at the end of 2025, Marty entered hospice while continuing to live in a memory care community in New York; kind and professional care made his last days more comfortable. Carl, Noah, and Sara were all with Marty on his final day, He passed in his sleep on January 24, 2026, having held on to his powers of speech, observation, and understanding, until his waning hours, as he would have wished it.

Donations in Marty’s honor may be made to Jews United for Justice (jufj.org ) or to the Society for Research on Biological Rhythms (srbr.org, especially its Global Fellowship Campaign). [Please disregard the links to its promotions that Legacy.com automatically adds. The family requests no flowers or gifts.]

Ruchel and Reuven had lost their first child, and each lost a brother, to the camps and the war. A twin sister was then born alongside Marty, but she did not survive the extreme hardship of their first months. Due to the disruptions of war, the earliest family or official documents begin only later, but January 10, 1944, is Marty’s consistent birth date, while birth locations named include Chernowitz, Bershad, and Secureni. As an adult, Marty’s own records were meticulous and organized. The decisive proof of the dementia that defined his last years lay in the disarray of his tax documents and piles of unsorted mail that his family encountered upon the first in-person visit in 2021 after COVID shutdowns.

As the Iron Curtain came down around 1946, Reuven insisted that the family flee West. They made their way eventually to a displaced persons camp in Italy, where Marty spent a couple of childhood years alongside his parents, maternal grandmother Scheindel, and Fanya, the widow of Ruth’s murdered brother, Moishe. There, too, was Fanya’s daughter Ada, who had survived the war in an orphanage in Bucharest and was miraculously reunited with her mother; Marty and Ada were as close as siblings. The family took advantage of whatever opportunities they could find in the camps, including a trip to ancient ruins that Marty pronounced boring as just “stones and bones,” which also rhymes in Yiddish.

Marty’s first language was Yiddish, with exposure to Russian and Italian, before learning English. He was known initially as Moishe or Musia, becoming Marty as an “American” name when he arrived in the United States, where his parents became Ruth and Reuben.

The family was able to come to the United States in Fall 1949 as refugees with a family sponsor, Ruth’s sister, Pola Greenstein (née Fish), who had been sent to the U.S. alone as a teenager just before the War. Fanya and Ada left for Israel. While most refugees traveled by ship, Ruth’s health was precarious. She still suffered from a back that had been broken by a German soldier’s rifle butt, and she was late in pregnancy. As a result, and with the assistance of HIAS (the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society), the family was able to cross the Atlantic by military cargo plane, with Marty’s first North American memory being the blast of cold air through an open cargo door as they stopped for fuel in Newfoundland.

Now enlarged by the birth of Marty’s brother Carl in November 1949, the family stayed a few years with Pola’s family in Providence, Rhode Island, while Reuben worked in a local store and then tried to establish himself in New York City. Marty’s memories from this time were largely of hardship, xenophobia, and catching sight of his father only in the middle of the night; he harbored a lifelong antipathy for Providence.

When Marty was in 5th grade, the family moved to the Bronx, where Reuben worked as a peddler/salesman, selling furniture in Spanish Harlem on commission/layaway, as he did for the remainder of his working life. Reuben learned to speak Spanish with a Yiddish accent, and his English lagged behind his Spanish. Ruth mostly cared for the family and home, but she was proud of her unusual educational achievements for her time, as an Old-World Jewish girl who went beyond high school to train as a pharmacist. Later, she would become an active and proud volunteer in many community settings.

As a Jewish, immigrant, non-native English speaker, and newcomer, Marty remembered being bullied by local kids in his Bronx neighborhood. He worked hard to learn unaccented English and excel in school. He attended Yeshiva (Jewish religious school) through 8th grade, where he graduated as valedictorian, made lifelong friends, and acquired a taste for argumentative contention and precision . He switched over to public school with his admission to the Bronx High School of Science. His parents drove Marty hard in school—he recalled reporting that he had scored a 98 on a test and receiving in reply, “what happened to the other 2 points?”—and were proud of his achievements; Ruth kept his report cards with her for decades. Marty was on his way to a scientific career, yet when he reminisced about his early education, it was his high school training in journalistic writing and his college coursework in the social sciences that he reminisced about most fondly.

The family struggled economically. Marty recounted not eating in a restaurant or taking a vacation until he was an adult. Although he was driven and excelled, Marty also experienced little control or say in his early life. After a teenage summer working in a US Post Office, he committed to avoiding any job where he had to ask permission to use the bathroom. Reflecting on his alienation when visiting Princeton while exploring college possibilities, Marty said that as a Jewish immigrant, he kept looking for the service entrance. He enrolled at Columbia, with the support of scholarships and the ability to live at home.

Marty met Marion Mund at Bronx Science, and they began dating at the end of high school. Shortly after he graduated from Columbia and she from Barnard, they married in 1965 at ages 21 and 20. Marty went on to Albert Einstein College of Medicine, on full scholarship in a new program allowing students to simultaneously earn an MD and PhD, in medicine and pharmacology, and gain a strong identity as a “Mud Phud.” At the same time, Marion earned her PhD in immunology at Cornell University’s New York medical campus. The couple moved on to Yale University, where Marty did a medical residency in psychiatry and Marion continued her research. Their first child, Noah, was born in New Haven in 1972.

Marty decided to pursue scientific research rather than medical practice. In 1974, he moved to the National Institute of Mental Health via a position in the federal Public Health Service. Thanks, in part, to that service and his parental status, Marty sidestepped direct Vietnam-era military service. At the NIH, Marty entered the field of research on circadian rhythms (the body’s daily cycle) under the mentorship of Nobel Prize winner Julius Axelrod, transitioning to a permanent civilian position and spending the rest of his career there. Much of his research focused on the regulation of melatonin production in the pineal gland, using cells extracted from chickens as a model organism. Devilish and averse to putting on airs, when asked by a stranger what he did for a living, Marty typically said, “I kill baby chickens.”

The family settled in Bethesda, Maryland, in a suburban neighborhood across the street from the NIH. Daughter Sara was born in 1976. While committed to providing his children an upbringing with more freedom and less hardship than his own, Marty also insisted that they not take it for granted, occasionally making a point of rejecting a creature comfort that, while attainable and conventional, seemed to him an indulgence.

Reuben died in 1978, and Ruth, who still suffered from chronic health problems, moved to an apartment in Rockville in the early 1980s to be closer to Marty and her grandchildren. When Noah and Sara were younger, she came over regularly to care for them, make dinner, and light Shabbat candles on Fridays. Marty and his mother had a devoted but difficult relationship, with Marty ensuring her care as her health declined and until her death in 2005. Ordinarily, they spoke English in front of others, but Yiddish was the language they reverted to for arguments.

Marty’s career was long and steady. He was known for being an excellent mentor to younger scientists and a valued interlocutor, though also quite intimidating intellectually. Colleagues consistently recall the sharpness of both his analysis and his humor, including a penchant for lobbing insightful but sometimes devastating questions from the back of lecture rooms at scientific meetings.

Marty was devoted to his science but eventually felt he was not flourishing at the NIH, leading him in 2004 to retire early from the lab. He continued joyfully for another decade as a celebrated editor of the Journal of Biological Rhythms (JBR), the main academic publication in his field. He threw himself into editorial work and continued participating in scientific meetings, especially those sponsored by the Society for Research on Biological Rhythms. A meticulous and demanding editor of research articles, Marty also explored his broader interests in the philosophical and institutional aspects of science by penning a series of probing and reflective editorials (preserved at srbr.org/publications/jbrish). Marty refused to take anybody, including himself, too seriously, and his mischievous and irreverent wit was reflected in his invention and publication of fictional letters to the JBR editor from meaningfully made-up writers, often chiming in to criticize one of Marty’s own recent editorials.

Noah and Sara both attended local public schools in Bethesda (Wyngate, Tilden, and Walter Johnson). The family had two cats in whom Marty had little interest, and later a beagle named Jessie whom Marty adored. The family regularly took trips into Washington DC for museums and cultural events, especially when hosting visitors. Marty often insisted on driving downtown rather than taking the nearby Metro in some kind of ritual and stubborn pride in being a New York driver who rejected his earlier reliance on the New York City subway. The family was distinctly neither athletic nor outdoorsy, though Marty tried gamely but not very successfully to do appropriately American things like go fishing with his son, often resulting in humorous and only mildly dangerous failures.

The family did not watch much TV or regularly listen to music. The radio was set to news, and there was no TV in the living room. Marty did not follow sports, but the family watched the Super Bowl every year because that was what you were supposed to do, though Marty was clearly more interested in Cosmos and National Geographic. The family was able to take a couple of big international trips, and a few more to marquee U.S. National Parks. Marty enjoyed travel and was an avid photographer, readily getting distracted or delayed, and enjoyed editing and curating slides for post-vacation slide shows.

With the crucial exception of air conditioning, Marty hated many “modern conveniences” that he deemed intrusive or unnecessary, and therefore the family was late to having an answering machine, VHS player, call waiting, CD player, etc. He didn’t see why he needed to answer the phone just because it was ringing, and Marty basically never used a cell phone even when everyone else really wished he would. He stubbornly resisted email for a while but eventually was worn down by his children when they left home; he later became a prolific correspondent and excessive forwarder of jokes.

Noah left home to attend Cornell for college, and then Sara went to Bryn Mawr. Marty was consistently proud of their academic and professional achievements while making clear that these were not what ultimately mattered most to him. He encouraged pursuit of passion over cautious instrumentalism. A few years after both children had left for college, Marty and Marion divorced.

Noah married Jessica Cattelino in 1995. Sara married Adam Nadel in 2009. Noah and Jessica are parents to Mica (16) and Rosie (14). They live in Culver City, California, where Noah and Jessica are both UCLA faculty, he in law, she in in anthropology. Sara and Adam are parents to Raya (13). They live in Jackson Heights, Queens, NYC. Sara works as the Artistic Director, Engagement for the non-profit theater company Pink Fang (formerly Ping Chong and Company), and Adam is a photographer and teaches history of photography at Queens College and other institutions. Marty loved his grandchildren dearly, delighted in teaming up with them against their parents, and endeavored to impart his love of Yiddish, wordplay, curiosity, and careful observation.

Around 2000, Marty met Marcia Bordman via a classified ad in the Washington Post, and they became devoted partners. In their early years, they enjoyed traveling widely together, including many destinations of their choosing across the U.S. and the world. Marcia would also accompany Marty to scientific conferences and enjoyed times with his friends and colleagues. Marty likewise became integrated into Marcia’s wide circle of friends in a dizzying array of reading, poetry, and study groups.

Marcia was an English professor at Gallaudet University, and they were a hilarious couple, their literature vs. science shticks coexisting with a shared foundation of intellectual curiosity, deep cultural pursuits, Jewish identity, humor, and love of language. More than anything else, they simply enjoyed one another’s company and could tell each other stories and analyze text together for hours, often to the detriment of whatever schedule they and others might have been on. As Marty suffered from dementia and Marcia from kidney disease, they were devoted to each other’s care as long as, and even beyond, when they were able. Even as Marty lost his way with simpler tasks, he somehow summoned the capacity to perform daily maintenance on Marcia’s complex home dialysis equipment. Marcia passed away in 2023, months after Marty entered a memory care community nearby.

Throughout his life, Marty retained a passion for intellectual pursuits, a sense of curiosity, a strong sense of ethics and Jewish culture and social justice values (without maintaining regular religious observance), a love for wordplay and Yiddish language and humor, and a disdain for physical exercise, green vegetables, and other forms of conventional rule-following.

He remained devoted to his family, and to the idea of the possibility of the “American Dream.” He always rooted for the underdog and loved a “David and Goliath” story. He was a bit of a contrarian, with facial expressions and tone that could seem dismissive or scary when he was just curious and furrowing his brows. He also could have a temper in the face of perceived foolishness, disrespect, or incompetence. He appreciated people who could go “toe to toe” with him with intellectual debate and/or wisecracks. Were he reading this, he would have a lot of editorial suggestions and criticisms, and would not be afraid to share them.

When people asked his hobbies, his family would say “his hobby was being smart,” which made the cognitive loss from dementia especially devastating. Nonetheless, he somehow maintained his essential qualities even as dementia robbed him of his memory of even his most basic biographical facts. While living in memory care communities, he observed, marveled at, and formulated curious questions about the world around him, especially the clouds and the trees. He urged his grandchildren to “pay attention” and “ask questions,” and he delivered endlessly earnest lectures about Yiddish usage, especially the word “takeh,” which means “really” but can have a million variations in meaning depending on intonations. He got and appreciated jokes, and demanded that questions be well specified. Inevitably, if a loved one or a medical professional asked how he was feeling, he would respond, “compared to what?”

Perhaps most movingly, even as the disease robbed him of precious time, there flowered in Marty a resolute kindness and gratitude for what remained. Even as he was poked, prodded, and assessed for reasons he did not understand, he consistently made a point of saying “thank you” and praising a job well done. When his grandchildren had to remind him not only of their names but their existence, he smiled warmly and said not only that he was delighted (if also surprised) to be a zeyde but that he was happy to be their Zeyde.

After a steep decline at the end of 2025, Marty entered hospice while continuing to live in a memory care community in New York; kind and professional care made his last days more comfortable. Carl, Noah, and Sara were all with Marty on his final day, He passed in his sleep on January 24, 2026, having held on to his powers of speech, observation, and understanding, until his waning hours, as he would have wished it.

Donations in Marty’s honor may be made to Jews United for Justice (jufj.org ) or to the Society for Research on Biological Rhythms (srbr.org, especially its Global Fellowship Campaign). [Please disregard the links to its promotions that Legacy.com automatically adds. The family requests no flowers or gifts.]

To order memorial trees or send flowers to the family in memory of Martin Zatz, please visit our flower store.

Martin Zatz's Guestbook

Visits: 44

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the

Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Service map data © OpenStreetMap contributors