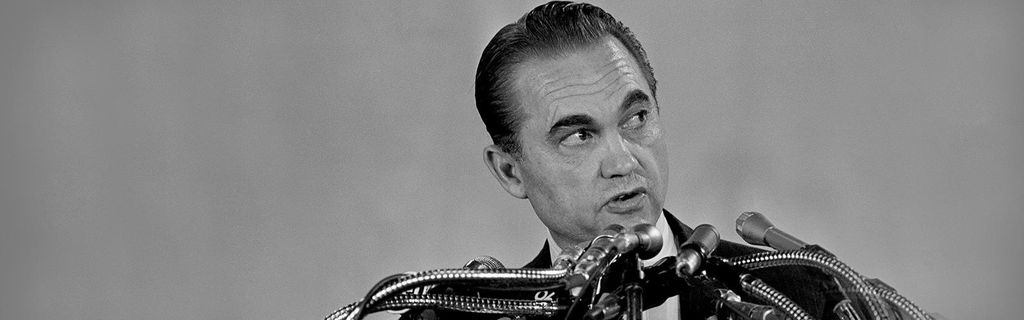

George Wallace: The Great Divider

by Legacy Staff

by Legacy Staff

4 min readAs another presidential election approaches, we remember a man who was as controversial in his time as any current candidate: George Wallace. In 2008 on the 10th anniversary of Wallace’s death, Jeff Frederick considered the evolution of his politics.

Ten years after his death, more than 20 years since he left office and decades after he became the most recognized governor in America, George Wallace’s complicated legacy continues to loom over Alabama, the South and the nation at large.

Wallace is still perhaps best known as a symbol of America’s resistance to the civil rights movement. Throughout the 1960s his candor and raw political acumen cast him into the role of defender of Southern traditions—namely White supremacy and segregation. But after a series of unsuccessful presidential bids and surviving a failed assassination attempt, Wallace pulled off perhaps the most astounding late career political reinvention in American history. He publicly apologized for his past, won a majority of black votes and earned a final gubernatorial term in 1982 as the most liberal candidate on the Alabama ballot.

For those who’d closely followed his evolution, perhaps the sudden about-face was not as surprising as it may first seem.

Born in sparsely populated Barbour County, Alabama, Wallace learned the staples of retail politics in the rural South and dreamed of becoming governor the way some kids hope to become NFL quarterbacks. After World War II service on a bombing crew in the Pacific, Wallace turned to electoral politics first as a state legislator and then as a judge. An instinctive campaigner—Wallace wrote Christmas cards to prospective Barbour County voters while still stationed in the military—the Alabamian had gifts for remembering names and details of voters’ lives and could sense the tenor of a room as soon as he entered it.

Raucous orator and master of political theater, he was fearlessly candid but also capable of tailoring his remarks to his audience, be they farmers and housewives at a county fair in rural Alabama, an antagonistic crowd of liberal Ivy League intellectuals, or a group of New Yorkers at packed Madison Square Garden. Though his speeches were often awash in vague generalities, the aplomb with which they were delivered showed first-class political stagecraft. After losing the governor’s race in 1958 campaigning as a moderate segregationist with the support of the NAACP, Wallace turned hard to the right on social issues. The move paid off, and he won his first gubernatorial election in 1963. During his inaugural address, he issued his most notorious statement, calling for “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Later that year, he would make his famed “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door,” a symbolic effort to prevent two black students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, from enrolling in the University of Alabama.

Wallace also honed a simplistic philosophy on the Vietnam War that resonated with some Americans: win or get out. Wallace won five Southern states and 46 electoral votes, nearly won two other states, and garnered more than 13 percent of the national vote. By this point he was too controversial, too much the pariah to ever be a serious contender for president, but many of his ideas eventually became staples of successful Republican candidates including Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush.

Wallace was many things: regional symbol of the White South, influential presidential candidate, segregationist, Alabama governor for a quarter of a century, repentant paraplegic, feisty campaigner. Those who loved him and those who loathed him—there was no middle ground—can agree on one thing: they remember him. His symbolism, the hate of a divided South and the hope of a united one, looms large over a state still reconciling its tortured racial past, a region trying to move beyond old wounds, and a nation caught up in a political divide between Red and Blue.

Written by Jeff Frederick. Originally published Sept. 13, 2008.

TAGS